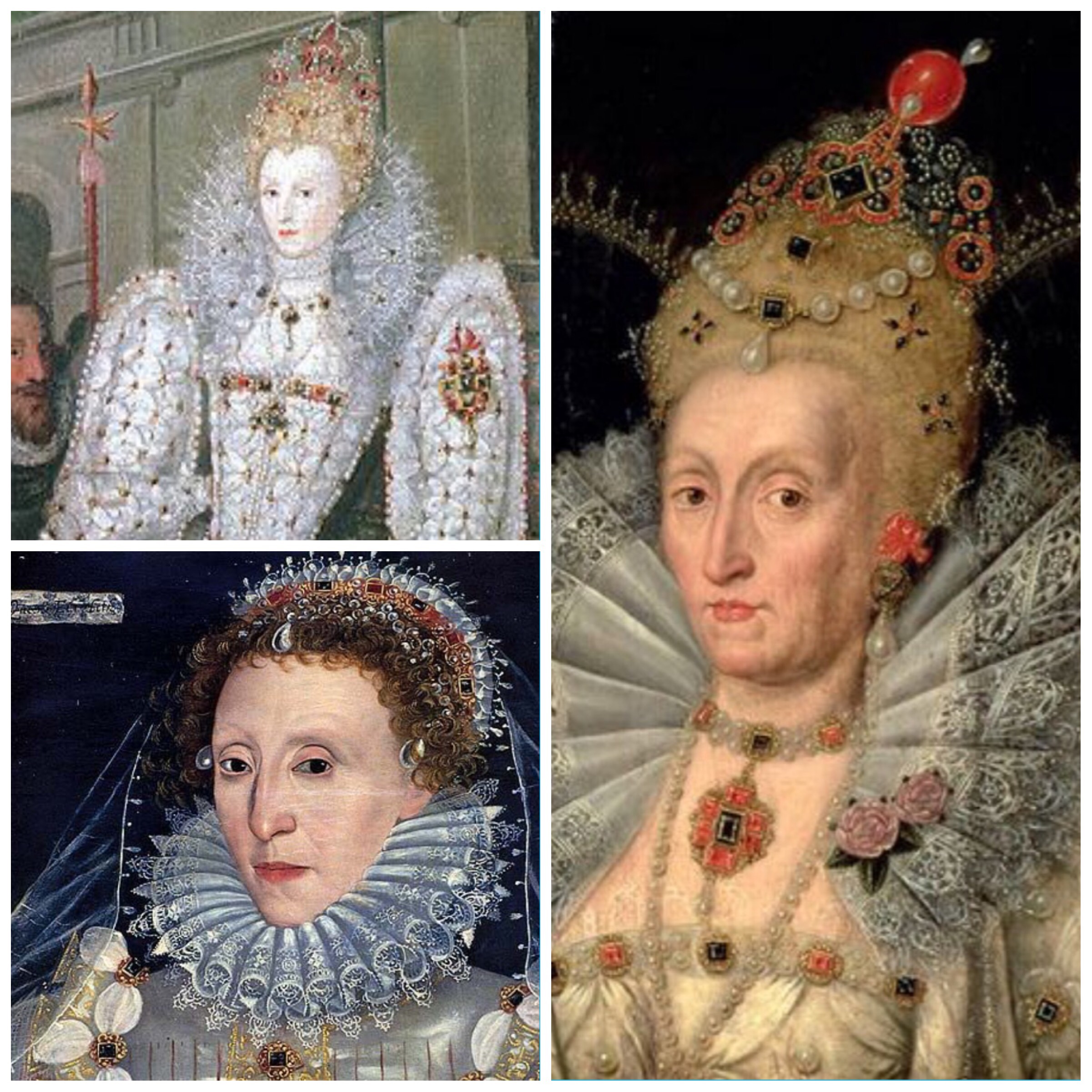

Queen Elizabeth I was amongst one of the most painted Queens. She is known for her iconic image as the Virgin Queen during her forty-five year reign from 1558 to 1603. Since then, historians have extensively studied Elizabeth and the motivation and reasoning behind her actions. For me, the most fascinating aspect of Elizabeth is the image she created for herself and the identity that others assigned to her. Specifically, I wanted to find out how the Queen and her court used clothes to establish these representations.

For unmarried women, necklines were quite low and often exposed a large part of the chest. Elizabeth took full advantage of these styles and kept up her image as a Virgin by wearing low-cut necklines.[1] Regardless of what else she wore, Elizabeth could immediately be identified as a virgin simply based on her necklines. Elizabeth even applied to her chest the same whitening make-up that she used for her face in order for it to appear smoother and whiter than it naturally was, especially as she got older.

As her reign progressed, Elizabeth wore more and more makeup to distract the court from her aging body. The sixteenth century beauty ideal was white, flawless skin. Therefore, every morning she would apply a whitening paste made with egg whites, powdered egg-shell, alum, borax, poppy seeds, and mill water to her face, neck, chest, and even hands- any skin that would be showing. [2] The Queen took great pains to cover up scars, pockmarks, and other defects and appear younger than she was. She also added vibrant wigs to cover her thinning and graying hair. These wigs allowed her to keep her iconic red hair well past the time of its natural color to appear as if she was not aging. She created an image of eternal youth, based on beauty that defied her age.

In 1597, when Elizabeth was in her sixties, the French ambassador observed that she had:

“…innumerable jewels, not only on her head, but also within her collar, about her arms and on her hands, with a very great quantity of pearls round her neck and on her bracelets. She had two bands, one on each arm, which were worth a great price.”

This amount of jewellery was not uncommon for Elizabeth and was a deliberate strategy of hers to distract from her aging body. She knew that her subjects would be awed by her magnificence so she played it up as much as possible and openly dazzled them through quality and quantity. In the 16th century, for instance, Elizabeth I not only used her clothes to denote her position and power by adopting the masculine doublet (the first power shoulders?), but also used fashion as an economic weapon, preventing foreign imports that would damage British trade.

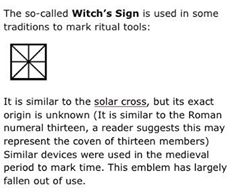

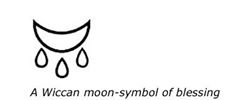

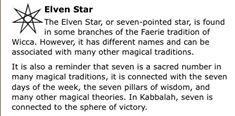

Her jewels for instance, symbolised more than sparkle or chastity. An example of this featured above. The jewels incorporated in Elizabeth’s headdress are:

- crescent moon with 3 pearl droplets

- square

- star

Within her court, Elizabeth was very conscious of color and its meanings and used them to her advantage throughout her entire reign. As part of the various editions of the Sumptuary Laws throughout the Tudor dynasty, only people of a specific social status could wear certain colours.

Elizabeth’s appearance stressed her rank as head of state and church and ‘pecking order’ was reinforced by legal restrictions:

None shall wear:

Any cloth of gold, tissue, nor fur of sables: except duchesses, marquises, and countesses in their gowns, kirtles, partlets, and sleeves; cloth of gold, silver, tinseled satin, silk, or cloth mixed or embroidered with gold or silver or pearl, saving silk mixed with gold or silver in linings of cowls, partlets, and sleeves: except all degrees above viscountesses, and baronesses, and other personages of like degrees in their kirtles and sleeves…

Sumptuary Law issued at Greenwich, 15 June 1574

These ‘Sumptuary Laws’ were originally brought in by Henry VIII and continued under Elizabeth until 1600. They were enacted to enforce order and obedience to the Crown, and to allow the assessment of status at a glance.

For instance, the privilege of wearing purple was reserved for the very highest echelons of society. When Elizabeth wore a purple velvet gown to her coronation feast, it very clearly indicated that she was now Queen. Simply the range of colors in her wardrobe indicated that Elizabeth only came from the highest social rank; no one else would have been legally allowed to own clothes in so many colors.

Fairly early on in her reign, she adopted white and black as her colors, which continually sent non-verbal messages to those around her.

White was the color of purity and virginity, but also the color of innocence and youth.30 When Elizabeth wore white, she identified herself as a virgin, who was young and energetic, despite her age. By evoking the purity of virgins, she built up her identity as a chaste woman. Her six ladies-in-waiting who attended her in public and entertained her often were all dressed in white also. By wearing the same color as her young and chaste handmaidens, Elizabeth identified with them and proudly proclaimed to the entire world that she was a virgin.

Elizabeth used black and white and their respective meanings together to exhibit the balance between youth and responsibility. She promoted herself as active and energetic, but also serious and capable of running a country on her own. She walked the fine line of work and play, business and leisure. Dressed in white, the dedicated ruler seemed forever young.

The greatest challenge to the argument that Queen Elizabeth I could have been a witch is that in 1563, she introduced the Witchcraft Act however, this fact is actually evidence in support of this argument.

The story begins long before she became queen, when her elder sister Mary was queen. The two were never close with Mary, both the daughter of Henry VIII but Mary’s mother was Catherine of Aragon while Elizabeth’s mother was Anne Boleyn. Mary was also 17 years older than Elizabeth.

Queen Mary was a Catholic and did all in her power to give primacy to the Catholic Church. She also acted to supress Protestantism through violent persecution, hence the well-earned acronym of Bloody Mary. The problem for Mary was that her sister Elizabeth held strong anti-Catholic, but being a princess could hardly be made subject to the Inquisition without raising a public outcry. This resulted in the Princess Elizabeth being held for a long period under house arrest and on March 8th 1554, Mary had Elizabeth imprisoned in the Tower of London. This imprisonment lasted for eight weeks with Elizabeth only being released when she agreed to put on an outward show of conforming to the Catholic religion.

Elizabeth though, had John Dee as her personal advisor. Born on July 13th 1527 at Mortlake, then a country village but now a suburb of London, John Dee was an enigmatic figure. An astrological chart marking the hour of his birth reveals that the Sun was in Cancer with the zodiacal Sagittarius was on the horizon. This combination favours scholarship and the study of secret sciences. Despite that many people challenge the veracity of astrology, this is a prophecy proven by his life to be highly accurate.

John Dee is accounted a great mathematician, scholar, philosopher and alchemist. To many serious occultists, his development of what is termed the, ‘Western Esoteric Tradition’ leads him to be viewed as the Father of modern witchcraft. This Western Tradition is the synthesis of astrology and ritual magic combined with alchemy to create a system of practical occultism. John Dee’s work provides the foundation for that of many later occultists and Dee certainly practiced himself. He is accounted as being adept at necromancy, probably the most difficult of occult practices. There is even a plaque on the house in which he lived, in Mortlake High Street, stating that, ‘John Dee the renowned necromancer lived here.’

To reveal the closeness of this relationship, there are numerous accounts of Elizabeth going to visit John Dee at his home. On 10th October 1580 she called to offer condolences on the death of his mother. Kings and queens don’t normally call at the home of ordinary people. Other various incongruities during Elizabeth’s life add to the evidence that she was his student in the occult as well as simply seeking his advice of other matters.

P. Rogers

She is called the, Virgin Queen, recorded as always saying she had a higher calling than becoming a wife to some man, put down by historians as being to the country, but those adept in the occult will see a parallel. She also consulted Dee to seek the most astrologically propitious time for her coronation. Subsequent history confirms the accuracy of this reading, but that she had this chart prepared reveals an interest and knowledge of the subject. Remember also that the practice of astrology is part of witchcraft.

All this indicates that a re-evaluation of the purpose behind the introduction of the Witchcraft Act is required.

Of course there can be no definitive evidence that Queen Elizabeth I was a practicing witch, though her reign did provide England with the foundation to turn it into a great empire, all against seemingly insurmountable odds. John Dee is known to have provided navigational information that helps the great explorers of the day, Drake, Hawkins, Raleigh etc. Queen Elizabeth I was a great queen and nothing can detract from what she achieved, but she was also a student of John Dee. Add to this all the other mysteries surrounding her life, there is ample circumstantial evidence to argue that Elizabeth I was indeed the true Witch Queen of England.

Incidentally, Elizabeth was very much interested in the occult. Dee was responsible for choosing the most auspicious date for Elizabeth’s coronation which was on January 15th, 1559.

Dee has been defamed through the centuries as a necromancer, but it’s the opinion of many writers that his angelic-cabalistic- alchemical work, his Philosophers Stone, the”Monad Hieroglyphica”(1564) may have been a cover for covert operations carried on in the name of her majesty. The 007 was the insignia number that Elizabeth was to use for private communiques between her Court and Dee.

Clues to this are revealed within her clothing and jewellery.

Elizabeth the first—the ‘Virgin Queen’, who wore reptilian motifs on her gowns.

Large jewelled serpent on her left sleeve holds from its mouth a heart-shaped ruby (allegedly Elizabeth’s heart) on a chain. On its head rests an orb, possibly the globe of the world or a celestial sphere. Elizabeth is holding a rainbow in her right hand, and the Latin inscription ‘Non sine sole iris’ on the painting translates as ‘No rainbow without the sun’.

This painting is well known for the eyes and ears which decorate her orange cloak. Less obvious are the equally numerous mouths. Since she was often referred to as the Virgin Queen, perhaps one should ignore the exceptionally vulva-like ear positioned over her genitals. “Elizabeth’s headdress poses a second problematic reading. The pale arc emerging from its top has been described both as an aigrette and as an ‘overarching ray’ of queenly light”. The hair style of the Queen with its “Thessalonian bride allusion. . . [contributes] to the sponsa Dei (wife of God) theme”.

The pelican was one of Elizabeth’s favourite symbols, used to portray her motherly love of her subjects. In times of food shortages, mother pelicans were believed to pluck their own breasts to feed their dying young with their blood and save their lives. The mother died in the process and during the Middle Ages the pelican came to represent Jesus sacrificing himself on the cross for the good of mankind and the sacrament of communion, feeding the faithful with his body and blood.

This myth is explicit: the Pelican is the sunlight of the Gnosis, the strength of Christ. The baby pelicans are humanity trying to connect to this force, but are still mutilated and killed by the force of the Demiurge, the “evil god” again. But by the sacrifice of Christ, the children of the Pelican will be saved, and the Beast mentioned—that is to say, the astral influences of the fallen world—is neutralised for the candidate who connects to the strength of the Gnosis

The phoenix is a mythological bird which never dies but, after 500 years, is consumed by fire and born again, making it a symbol of the Resurrection, endurance and eternal life. Only one phoenix lives at a time, so it was also used to symbolise Elizabeth’s uniqueness and longevity.

As mentioned above pearls adorned her clothing (because of their resemblance to the moon) were used to present Elizabeth as the goddess of the Moon, Cynthia (also known as Diana), who was a virgin and therefore pure. Sir Walter Ralegh helped to promote the cult of Elizabeth as a Moon goddess with a long poem he wrote during the late 1580s, ‘The Ocean’s Love to Cynthia’, in which he compared Elizabeth to the Moon.

In pre- Islamic and Christian mythology, the Roman Goddess Diana like Venus was portrayed as beautiful and youthful. She wore the Crescent Moon as a diadem. It is a major attribute of Goddess Diana. In Roman mythology, Diana was the goddess of the hunt, the moon and childbirth. She was equated with the Greek Goddess Artemis, Diana was worshipped in ancient Roman religion and is revered in Roman Neopaganism and Stregheria [Ancient Etruscan Religion of Witches]. Dianic Wicca, a largely feminist form of the practice, is named for her. Diana was known to be the virgin goddess of childbirth and women. She was one of the three maiden goddesses, Diana, Minerva and VESTA , who swore never to marry.

Elizabeth was also often associated with Minerva (or Pallas Athena), who was the virgin-goddess of war and defender of the state. Although prepared for war, she preferred peace and came to stand for peacefulness and wisdom. She was also the patron of arts and crafts, especially wool, and of trade and industry, including shipbuilding.

A late 16th century portrait of Queen Elizabeth I has revealed over time and degradation that she was originally depicted holding a coiled serpent in her hand instead of the innocuous nosegay she holds now. When an earlier image that has been painted over begins to show through, that is known as a pentimento, which means repentance in Italian.

The portrait, painted by an unknown artist, some time in the 1580s or early 1590s, has not been on display at the National Portrait Gallery since 1921. You can clearly see the shadow of the serpent’s coming up from between her fingers and his tail coiling above her hand.

The serpent was a symbol of wisdom and reasoned judgment — as on the rod of Aesculapius, the physicians’ emblem — so that’s probably where our unknown artist was going with the imagery. He changed his mind, though (possibly in consideration of the common association of snakes with the devil and original sin), and quickly painted it over with a strangely-shaped but perfectly inoffensive little bouquet of roses.

Paint analysis shows that the snake was definitely made at the same time as the rest of the portrait. There is no varnish between the snake and flower layers, so we know it was painted right over.

Ultimately, Elizabeth’s fashion transformed her into a living, breathing icon. Or rather, iconostasis: there’s no way she could move much in the tightly whaleboned stays and enormous sleeves, padded, slashed and pricked with precious gems, that fill the frame of Sir Nicholas Hilliard’s Phoenix portrait. There’s even something of the might of her father Henry VIII in the width of those shoulders. They say warrior as much as wealth. Power dressing, in every sense of the term.

Beyond the veil: X-rays reveal that Queen Elizabeth I was originally painted wearing an elaborate wing-like veil, but this fashionable feature was painted over in the eighteenth century to make her look more modern. This line shows where the veil was on the original portrait and traces of lace can be seen

This portrait shows an unmistakably ageing Elizabeth, her wrinkles unconcealed by makeup, with heavy, dark lines under her eyes. The reality of fleshly deterioration and melancholy age is revealed almost as brutally as in a notorious portrait of the present Elizabeth by Lucian Freud.

Elizabeth stands in a silver dress on top of a map of southern England, a beautiful colossus seen against a stormy sky in which the sun is breaking through. The story behind this painting reveals the culture in which Elizabeth had to be beautiful.

By choosing her outfits, and literally creating her public image each day, these women shaped a nation. Without the preparation every morning, Elizabeth could not have faced the world and ruled her country effectively as she did. She needed to create her image in order to be successful politically

Twig, 2015

Sources

[1] Weir, Life of Elizabeth I, 234-235.

[2] Weir, Life of Elizabeth I, 236.

- http://fashion.telegraph.co.uk/article/TMG11110751/Power-dressing-how-do-women-get-ahead.html

http://www.elizabethancostume.net/influence.html http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2753550/Queen-Elizabeth-I-s-secret-outfit-X-ray-famous-Tudor-portrait-reveals-wing-like-veil-hidden-18th-century-airbrush.html#ixzz4EiFrJTl2 - http://www.rmg.co.uk/discover/explore/symbolism-portraits-elizabeth-i